The information security community loves lists, cycles, and other guides for actions. We have important steps that need to be followed, but no investigation is exactly the same, and every one requires a bit of improvisation.

So how do you balance these needs? The paradox of disciplined steps mixed with room to adapt to a situation. Lots of groups are posing solutions, some useful, some not so useful, and some 100% misconstrued. I’m going to take this week to break down a number of the most common cycles and processes including OODA (keep reading!), the Intelligence Cycle, the Cyber Kill Chain, & F3EAD.

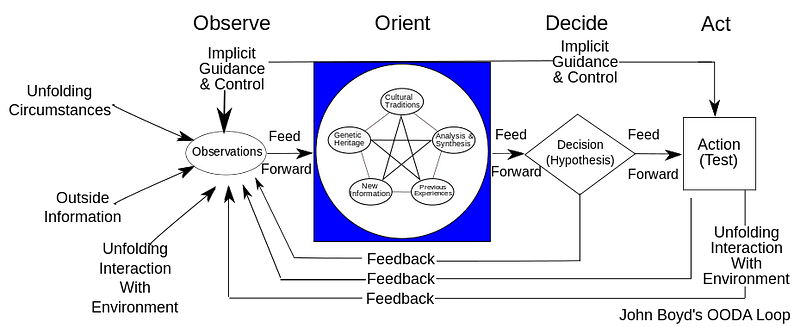

The OODA Loop

OODA is easily the most misunderstood cycle on this list. It is simple but powerful, so powerful it causes people to want to over think it. At it’s core OODA is an abstraction of the typical human thought process. Developed by American fighter pilot and tactician Col. John Boyd to understand fighter engagements the OODA loop is applicable to most decision cycles, including incident response decisions.

From Wikipedia: OODA Loop

While the annotated version above is complex at it’s core the OODA Loop is made up of four simple steps.

| Observe | Gathering data that may be relevant for action. |

| Orient | Next information is contextualized by the decision maker. |

| Decide | Finally based on the contextualized data a decision is made. |

| Act | The decided upon course of action is carried out. |

At this point the cycle restarts based on observing the results of the action.

OODA in Incident Response

“Under OODA loop theory every combatant observes the situation, orients himself…decides what to do and then does it. If his opponent can do this faster, however, his own actions become outdated and disconnected to the true situation, and his opponent’s advantage increases geometrically.” — John Boyd

So how does this actually apply to incident response? In a tactical sense this happens all the time:

- Observe: Monitoring via network (Intrusion Detection), system (Anti-virus), and environment sensors (Social Network Monitoring).

- Orient: Data is compared against known bad indicators, known good white lists, and considered based on analyst experience.

- Decide: An analyst decides what to do based on data discovered. This could be to decide it is a true positive (start remediating), a false positive (make a plan for tuning), or inconclusive (gather more data).

- Act: The analyst initiates their plan to either start remediating, request tuning, or continue gathering more data.

And the cycle begins again. Where this gets even more fascinating is when you compare this against the OODA loop being carried out by an attacker:

- Observe: The attackers gather information based on implants, usually including scanners, keyloggers, etc.

- Orient: Access available is contextualized based on goals at the current phase of a compromise, whether persistence is achieved, if current access is specific, etc.

- Decide: The attacker makes a plan to expand their access, solidify current access, evade investigators, or complete objectives (steal data, turn up centrifuges, etc).

- Act: The attacker executes their plan using the capabilities they have available.

These two loops are running simultaneously, competing with each other every second. The fact is whichever actor can complete this loop faster, continuously, will be most likely to achieve their objective. Over time it is almost guaranteed that a group that OODAs faster will always have the decision/action advantage, and thus more likely to be more successful. The big caveat to this is in an adversarial setting these loops are occurring simultaneously, meaning that the data collected during the observation phase might not be accurate by the action phase. This is why the relative speeds each actor can complete the loop are so key.

Takeaways from OODA

The great thing about OODA is it gives us a framework to talk about how we make decisions. At it’s core the thing Col. Boyd was able to show in a concrete way something everyone implicitly understands: whoever makes decisions and acts fastest has a distinct advantage.

“The future has already arrived. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.” — William Gibson

For incident response our goal needs to ultimately be to OODA faster than attackers. In most cases at it’s core improving a DFIR capability is all about being able to OODA faster as a team. New sensors improve your ability to observe while threat intelligence data improves orientation. You can’t really put OODA into practice, but it can be used to structure how you think about decision making, and what you can do to improve the speed with which you make decisions.